Hi there:

Welcome to the second issue of Gushi. Thanks for being here.

In our second story set against the coronavirus outbreak in China, we move from the fringes of hard-hit Hubei to the provincial capital Wuhan, the center of the epidemic that is still under lockdown.

As the situation in China appears to come under control and the focus shifts to the surge in cases elsewhere in the world, this piece published by the non-fiction platform The Story Plan on Feb. 14 chronicles the trials of a Wuhan couple in the early days of the local crisis. The husband’s parents fall ill in succession, with the father eventually testing positive for COVID-19.

Perhaps the biggest takeaway from the story is the relative scarcity of medical resources in China despite its economic boom in recent decades, even in a big city like Wuhan. The narrator—the wife—tells of the couple’s inability to get quick testing and secure hospital beds for the elderly couple despite their severe condition.

—ML

China Outbreak: A Wuhan Couple’s Blood, Sweat and Tears

By Ji Xiaoyang, as told to Jin Shian

Edited by Pu Moshi

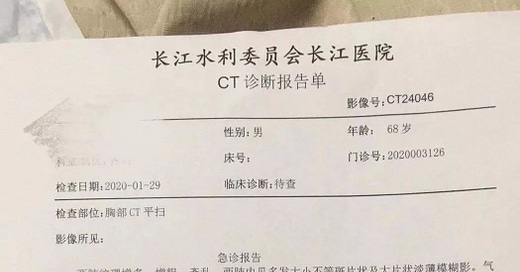

The results of the author’s father-in-law’s CT scan at a Wuhan hospital. Photo by author.

1.

This is a second marriage for both Wang Bo and I. We got registered just six months after we met. Our wedding was basic. The wedding banquet took up two tables, with only close relatives invited. Before we got married, Wang Bo’s mother said: “His temper is bit odd.” But the only thing that stands out about him is his loud voice and bluntness. Most Wuhan men are like that.

I don’t consider Wang Bo’s temper weird. Sometimes he’s even a bit soft. Once we were window shopping at a mall and he disappeared. After an extensive search, I found him stooping by the entrance to the mall. I asked him what was wrong. He said he saw his ex-wife. I lashed out immediately. “And? Are you ashamed of me?”

He is a technical expert. I own a flower shop and make the occasional overseas trip as a surrogate shopper. We own a car and an apartment, quite the normal life. We got registered on Nov. 12, 2013. This is the seventh year of our marriage. Despite all the talk of the “seven-year itch,” we treasure our relationship dearly because it’s a second marriage for both of us.

In the wee hours of Jan. 23, the chat group my insurance agent set up for his clients was abuzz with talk that Wuhan was about to go into lockdown. I am a light sleeper to begin with. That night I was glued to my phone. I turned numb from the information overload, which aggravated my anxiety.

After tossing and turning for several hours, I told Wang Bo about the lockdown when dawn finally arrived. He was still lingering in bed and seemed absentminded. I quickly put on a long, black down jacket, a white surgical mask and a blue shower cap, so I could go shopping for groceries at the supermarket chain Metro, a small shopping cart in tow. At that hour Xudong Street was completely empty. Another similarly dressed person pressed forward on another sidewalk.

While nary a pedestrian could be found on the streets, the supermarket was packed. I braced the crowds as I fought for my selection of veggies, fish, meat and frozen foods. Long lines trailed the checkout counters. Everyone was wearing a mask and waiting patiently.

After I got home, I uploaded the footage I shot onto TikTok. I kept monitoring my phone, watching the number of views on my video spike until it surpassed 30,000. I raised my phone, turned toward Wang Bo and said: “Hey, do you think I’m going to become a web sensation?” Wang Bo didn’t move as his thumb glided along his phone monitor at a measured pace. “Are you trying to get people pissed off at the fact that you’re out and about in these conditions?” he asked. The thought of me fighting my way to our groceries while he goofed around at home infuriated me. I grabbed him by the collar, stuck my phone in his face and forced him to watch my video from start to finish.

Unimpressed, he said: “You got this many views because everyone is stuck at home and bored.”

Our custom is to have dinner with my parents on Lunar New Year Eve and head to his parents’ place on Lunar New Year Day.

The lockdown meant we couldn’t go anywhere. But still anticipating our visit, my mother cooked 10 dishes and a soup dish in keeping with her tradition. When she called to tell us dinner was ready, I let out a deliberate sigh. “Open your eyes! How are we going to get over there? Fly?”

When we ate at home, my mother sent pictures of the sumptuous meal she prepared. The table was filled with my and Wang Bo’s favorite dishes—preserved meat with tarragon paste, pork chop and lotus root soup, steamed meatballs and so on. I started to cry.

Wang Bo couldn’t help sticking his foot in his mouth again. After playing around with the rice in his bowl with his chopsticks for a while, he said, “There’s nothing we can do about it. We have to stay put. The moment we set foot outside we’re exposed to a mobile risk factor.” I told him to shut up and ordered him to wash the dishes.

2.

On Lunar New Year Day, Wang Bo’s little sister called (I like to call her “Little Auntie”). “Our eldest’s teacher has been diagnosed with the new disease. Word has it a parent whose child attends the same taekwondo class as our younger one is a suspected case. How come so many cases popped up around us? What should I do? Our eldest loves sitting in the front row in class.”

I asked frantically: “The kids don’t have symptoms though, right? Don’t head out no matter what. Just stay put at home.”

Little Auntie said: “No symptoms, but Dad had a low fever—38.1 degrees Celsius. The fever retreated after he took flu medication for a few days.”

Wang Bo and I live in the Wuchang region of Wuhan. Little Auntie and her family and my in-laws live together in Hankou. My father-in-law helps chauffeur the kids. Little Auntie and I concluded that he fell victim to the flu in between seasons because his immune system was weak from having survived bladder cancer. The kids didn’t have symptoms, nor had he come into contact with any confirmed patients.

Wang Bo, who was listening to our call while lounging on the couch, got up quietly and retrieved the spray bottle we use to water plants from the balcony. He washed it, poured in a cap full of Dettol and diluted it with water, then screwed the bottle and shook before spraying the floor and our furniture.

I was thoroughly amused. “OK, Wang Bo is starting to get nervous. Is he the most chickenshit member of your family?” I asked Little Auntie. After hanging up, pointing to the orchids on the tea table, I said: “Hey, watch it. I just bought those.”

Wang Bo didn’t respond. Spray bottle in hand, he ran out of the apartment. After a while, he resurfaced, yelling in the direction of the kitchen, where I was preparing our next meal: “We’re out of antiseptic. I’m going to get a refill. If you’re in a hurry to go out, remember to use the elevator on the left.” I stuck my head out of the kitchen. “Are you perhaps being a bit too harsh?”

When we were watching TV that night, Wang Bo, who was holed up under a blanket, removed a thermometer from one of his armpits and examined it under the lights. “I think I have a fever too.” I went silent briefly before sticking out my hand. Wang Bo tossed the thermometer onto the tea table instead and said: “Don’t touch. Where are the masks?”

Heading in the direction my hand was pointing, he took a few steps toward the dresser by our front door before pausing abruptly. “You better fetch them. Put on one yourself, then toss me another.”

Wang Bo had checked his temperature three times since Little Auntie called. I felt like he had willed his fever into existence. I asked for confirmation. “Are you sure you have a fever?”

Wang Bo put on his mask and made the bed in our guest room. Standing in the guest bedroom, he stared at me aloofly, as if mentally building a moat between the two of us. “Keep your mask on. You can’t take it off even when you go to bed!” he barked.

Come bedtime, my muffled voice emerged from behind my mask sounding like static. “I’m not sure if I can pull this off. How am I supposed to breathe?” Wang Bo replied solemnly. “I can do it.”

3.

Thus began Wang Bo’s self-imposed quarantine in the guest room.

The only time he opened the door to the room was to pick up his meals. I would leave his rice and dishes by the door, retreat a few steps before Wang Bo opened up and retrieved the meal. Those were only the times during the day I caught a glimpse of his mask-covered face. When I collected his utensils and dishes after a meal, Wang Bo would sometimes yell from behind the door: “Remember to spray antiseptic at my doorway.”

Even though we didn’t complain about the arrangement—nor were we a young couple madly in love—the fact of living together but being so far apart at the same time broke my heart.

Wang Bo refrained from speaking to me directly, resorting to WeChat messages instead: “Our situation isn’t that bad. Look at my classmate Li Ming. Someone at his company was diagnosed. Now he’s living in his car. He has two kids, but he’s too spooked to head home.”

Our quiet routine was completely upended. I felt extremely anxious everyday. Wang Bo was taking Lianhua capsules—a type of processed Chinese medication—and a cephalosporin antibiotic daily. But if he had the new type of pneumonia, this drug regimen may not work. An old classmate told me that you could get Arbidol tablets at the Xinte Pharmacy on Hangkong Road, but we didn’t have access to our car.

I considered our options. All our friends had their hands full. Little Auntie’s family had a car, but my father-in-law was still feverish on and off, plus she has two kids. She was completely bogged down, barely able to manage three square meals a day.

On the 28th, my father-in-law couldn’t catch his breath when he got up from bed and collapsed. Oblivious to the risk of getting infected, Little Auntie took him to the ER at Wuhan Union Hospital.

By the time she arrived, she could already see the long line for fever patients snaking out of the ER entrance. She had no choice but to turn around.

On the 29th, Little Auntie took my father-in-law for a chest CT at their neighboring Changjiang Hospital. The diagnosis: both his lungs were infected, the final diagnosis pending further lab work.

At that point we felt we had caught a break. Maybe it was regular pneumonia. After getting home, Little Auntie put in a request with neighborhood management officials to have my father-in-law undergo nucleic acid testing for the new strain of coronavirus.

We still had to go about our lives. Little Auntie and I agreed to put me in charge of meals for both families. I got up at 6 every morning, boiled a pot of bottled water and inserted pieces of chicken, removed the foam and added ginger spices and wolfberries. After letting the soup cook on low fire for several hours, I added a bit of salt and pepper. Sometimes I made pork chop and lotus root soup instead. I would save a bowl of soup for Wang Bo, make two additional dishes and pack them up for Wang Bo’s brother-in-law to pick up at 9 a.m. after the drive from Hankou.

Back then, Wang Bo was still in good spirits. Sometimes he would even complain the soup was too salty or hadn’t been let to boil long enough. Still, he was sensible enough to count his blessings and finish his soup every day.

4.

On Feb. 1, my mother-in-law started developing fevers.

Little Auntie was on the verge of a breakdown. My father-in-law was struggling to breathe after a mere few steps or whenever he exerted himself. He was basically out of breath all day. Someone had to be with him all day. I said: “Why don’t I take Mom to the hospital. Wang Bo’s condition isn’t that bad. But I still don’t have access to a car. We’ll have to ask brother-in-law for a ride.”

Wang Bo was stuck at home anyway, so we decided not to tell him about his parents until there was a conclusive diagnosis. In the morning, I still prepared lunch as usual, knocked on his door and said: “I’m heading out for groceries. It could take a while.”

Having been holed up at home for several days by then, Wang Bo didn’t know that our grocery shopping was already being done for us. The owners’ association in our residential complex asked a vegetable vendor to make periodic deliveries. Every household was uniformly issued a bag of veggies containing seven or eight varieties. On top of the cost of the veggies themselves, each unit paid another 35 yuan (US$5) for transportation. A board member from the owners’ association wrote in our chat group: “Whoever goes grocery shopping now on their own is a selfish prick.”

Wang Bo responded from behind the door: “It says in the news that your eyes are vulnerable too. Why don’t you wear a pair of glasses too?”

Heeding his advice, I wore a pair of glasses that protect against blue light. My brother-in-law picked me up first before we went for my mother-in-law. My mother-in-law was wearing a red down jacket and holding a blue canvas bag. She spoke and walked effortlessly, her only giveaway being a slightly feeble voice.

My mother-in-law said: “It’s just a low fever, only 37.8 degrees Celsius. You don’t have to get too worked up. I would have skipped the hospital altogether if it weren’t for this epidemic. How’s Wang Bo doing at home?” I responded: “He’s OK. He’s been checking his temperature three times a day the past two days. He no longer has a fever.”

The roads were completely empty. My brother-in-law drove very fast. The parking spots in front of Union Hospital, however, were already taken. My brother-in-law dropped us off and asked us to call ahead of time shortly before we were done. He had to get back to take care of the kids. We had a meticulous division of labor.

When we set foot in the hospital at 8:15 a.m., the nurses manning the reception desk in the respiratory medicine department were surrounded by dozens of patients and their family members. The benches were already crammed with patients. Some of the patients without seats settled for the floor or curled up in their wheelchairs. Some family members kept trying to weave through the crowd at the reception desk and threw glances at the doctors’ office. That led nowhere because the doctors’ office was locked.

After finding a seat for my mother-in-law, I pressed the edges of my mask against my face and went to work. First, I picked up a number for my mother-in-law to get her temperature taken. Then a young intern ordered tests. We lined up for a CT. It wasn’t until 5:30 p.m. when we were finally greeted by a Dr. Lu.

The CT revealed “areas of infection on both lungs indicated by multiple blots.” Dr. Lu said “both lungs had multiple dense, tinted-window like blots.” This was a classic symptom of the new form of pneumonia.

Dr. Lu asked me if anyone else in the family was sick. After learning about my father-in-law’s condition, he said he suspected both my in-laws were likely cases and suggested they get nucleic acid tests immediately.

I told him in a resigned tone that our residential complex was issued a quota of just 21 tests in one go. My father-in-law had been in line for more than a week. I complained to local neighborhood officials and called the mayor’s hotline. Neighborhood officials said my father-in-law’s CT report didn’t contain the all-important “tinted-window like” wording, which is why he kept getting bumped back.

There was nothing Dr. Lu could do, but he said that my father-in-law’s case was now stronger in light of my mother-in-law’s CT report.

Dr. Lu kindly gave me his private WeChat account. He said he was on loan from a hospital from Guangdong and that handing over his contact information wasn’t standard protocol—but an extraordinary measure. He said we could write him with questions about patient care and he would get back to us as soon as he could.

5.

The author’s husband (wearing a backpack) loads the family car as he prepares for the drive to his younger sister’s apartment in another part of Wuhan. He decided to move in with his sister temporarily to help take care of his ailing parents. (Photo by author).

After we left Union Hospital and broke free of the crowds, we felt a sudden drop in temperature. The icy cold crept up from my sole of my feet, inch by inch. My soaked mask clung to my mouth.

My mother-in-law was feeling quite weak. As soon as we exited the hospital, she sat down on the edge of a raised flower bed. I asked if she felt cold. She waved her hands, then supported herself by placing her palms over her knees, sitting in silence.

I kicked myself for forgetting to call my brother-in-law ahead of time, but in hindsight I realized I never would have found the time anyway. I told my mother-in-law in an apologetic tone: “Mom, I’m calling brother-in-law now.” She didn’t say anything. Not pausing to consider the risk of infection, I felt her hand, which was cold.

When my brother-in-law arrived to pick us up, he told us that Wang Bo was up to speed on the latest. Suspicious because I was away for so long, Wang Bo had called his sister. After he was briefed, he consoled his father.

I pushed open the door to our apartment at 8:30 p.m. Wang Bo heard the commotion. He ordered frantically: “Take a shower and wash your hair now. Toss your laundry in the washing machine and leave your handbag on the balcony. Remember to use lots of 84,” referring to a local brand of antiseptic solution.

When I emerged from the bathroom, I could hear Wang Bo wailing in his room like a trapped beast. Having just shed my protective gear, I was in a daze, or maybe I was too tired. I didn’t have the energy to cry. But if I had started sobbing, maybe Wang Bo would have stopped. Instead, I waited patiently for him to finish venting.

On Feb. 3, a WeChat friend reposted an ad from the American drug company Gilead Sciences recruiting test subjects for the third phase of the clinical trials for the antiviral drug Remdesivir. (Gilead Sciences is testing the drug on COVID-19 patients in China.) I asked Dr. Lu what he thought. He said drug trials were conducted on a double-blind basis, meaning half of the patients were fed sugar pills. He suggested my in-laws stick to their existing drug regimen.

On Feb. 4, my father-in-law’s blood-oxygen level dropped to 88. After using a ventilator, it rose back to 94. Dr. Lu said that was a decent level, ordering my father-in-law to lie down or maintain a reclined position around-the-clock, skipping trips to the bathroom to the extent possible, and to breathe with his nose as much as he could.

On Feb. 5, my in-laws needs could no longer be met by a single ventilator. I ordered the Xinsong brand ventilator on JD.com on Dr. Lu’s recommendation. After I placed the order, I began fretting whether it could be delivered amid the lockdown.

On Feb. 6, my in-laws were finally scheduled for nucleic acid testing at the Hubei Provincial Hospital of Integrated Chinese and Western Medicine. But they both tested negative for COVID-19, which meant they didn’t meet the criteria for hospitalization.

Wang Bo, who was no longer feverish, also emerged from the guest room that day, but he still insisted on maintaining a 2-meter buffer between the two of us. He said: “I had no choice but to lean on you before. Now I will start taking my parents to their hospital appointments. I’ll be a big risk factor, so I plan on moving to Hankou temporarily. You should stay put. You’re the only child. You still have your mom, dad and granddad to take care of.”

I knew that being the oldest son, the big brother, once that Wang Bo felt he was OK, he would rush to be by his parents’ side. I lowered my head in stubborn defiance, but I didn’t know what to say. Wang Bo said with a smile: “If anything happens to me, the apartment goes to you.” “What the hell do I want the apartment for?” I retorted.

I saw Wang Bo off from the entrance to our apartment building. Wang Bo pointed to a spot on the sidewalk and said: “Don’t go beyond that point.”

I watched Wang Bo’s skinny frame bend over to load his personal belongings into the trunk of our car bit by bit. He’s 1.78 meters tall and weighed just 121 pounds before we got married. He’s gained some weight since then. His face is rounder. He was born with a deformed gall bladder, which he had surgically removed last year so his bile duct and intestines could be fused. That cost him another dozen pounds or so.

The backpack Wang Bo was carrying contained his medical history and his health insurance card. He was prepared for the worst-case scenario. He said before driving off: “If I’m infected, I’ll apply to be admitted into one of the makeshift hospitals in Wuhan.”

When I returned to our flat, it was already dark. I didn’t turn on the lights. Something in my head snapped the moment I shut the door.

I broke down in tears on the sofa.

6.

On Feb. 7, Wang Bo moved into his sister’s place to help take care of his parents’ daily needs. They were taking the antiviral drug Oseltamivir and antibiotic Moxifloxacin hydrocholoride tablets, Lianhua capsules and continuing use of the ventilator. He was also taking them to the neighboring Hubei Provincial Hospital of Integrated Chinese and Western Medicine by wheelchair for globulin injections.

My mother-in-law’s condition fluctuated. My father-in-law had been sick for nearly three weeks. By contrast, his condition was quite severe. A single ventilator wasn’t enough to cope with both of them. Online tracking showed the ventilator I ordered had already arrived in Wuhan three days ago, but there was no one to deliver it door-to-door. All I could do was stress myself out.

Both my in-laws struggled with lack of appetite and had difficulty breathing. They barely ate. Yet both of them were older than 68, which was the cutoff for the temporary hospitals being set up in Wuhan to handle the huge surge of patients.

My brother-in-law approached community officials about my in-laws’ case repeatedly. The community liaison officer said both of them had already been logged in the database, but they had to meet the hard criteria of two positive tests and conclusive CT results.

I could only leave my contact information on the Weibo messaging board for pneumonia patients and the community-building app Weilinli. I also eventually tracked down the author and poet Wu Ang, who was assisting patients on her own initiative. She help me set up a WeChat group asking the public for help.

Wang Bo was too busy to chat. He left me the occasional message, “hang in there” being the most frequent one. If we had extended down time, we would compare notes on the other patients’ messages on Weibo and encourage each other by saying that our situation wasn’t an exception nor the worst.

Gradually, we received many kind offers, but the deluge of messages was also overwhelming. I could only post a blanket response: “Thanks for everyone’s concern. My in-laws are being cared for under the guidance of doctors. We’re not in a position to prepare traditional Chinese remedies, so no need to post them.”

On Feb. 10, the results of my father-in-law’s second nucleic acid test were issued. He was positive, which finally won him admission to Hankou Hospital. On the same day, my mother-in-law tested negative again and had another CT scan. The result was still “multiple tinted glass-like shadows on both lungs.” She fell short of admission criteria again.

On Feb. 12, with the help of volunteers, my mother-in-law was finally admitted to Hankou Hospital as well. Wang Bo sent messages of thanks to the volunteers. I also thanked Dr. Lu via WeChat. Dr. Lu responded: “Just doing my job.”

After getting his mother settled, Wang Bo sent me a picture of the box meal the hospital issued her. He wrote: “The meal is OK. Mom and Dad’s appetites have improved. If all goes smoothly, we can see each other again at the end of the month.